The Scriveners Review.

For the Murray Mallee and Regions …. Vol. 1…#5.

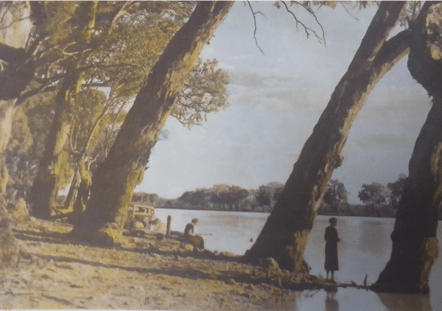

(Fishing on the banks of the Murray River..1935.)

Under the Mallee Bough,

Across the quiet waters,

Blended with the cries of river birds,

We hear our ancestral voices.

A selection of poems and stories by local writers.

Our motto: “ Art not just for art, but for culture’s sake”

Selected and edited by Helen Tuxford and Joe Carli.

KOOKABURRA MORNINGS.

Each morning two kookaburras sit

In the tall gum tree,

And waken the grey morn

Singing their mad, joyous song;

Hailing the sunrise,

Carolling the dawn.

‘Go back to sleep,’ I tell them,

Woken too early ,

For the tall gum tree,

‘Tis not far from my window.

But they never harken to me,

‘’If a kookaburra calls

Three days in a row,

It will rain.’

I know now that’s nonsense,

For every morning, two kookaburras sit,

In the tall gum tree,

Singing their mad, joyous song,

Heralding the new day,

Carolling the new dawn.

They’re singing and calling,

Greeting the morning,

Carolling the dawn. (Helen Tuxford.)

Precious. (Ambrose Quint.)

I wrote this yarn up a long time ago, this is one of those classic

“blow up the dunny” yarns that were more prevalent in the days of

“knock-about” working camps and such. I doubt the modern facilities used

on outback work camps would need such desperate action (thank you

Unions!)….but I remember such site dunnys when at distant building jobs.

Precious.

Precious

was a “travelling stores requisitioner and supplier” for a large

mineral drilling company . He was called “Precious” because of his

penchant for slapping on the after-shave and a Dandy for the attire…In

town it would be “Fletcher Jones” and Julius Marlow..out back it was

strictly R.M.Williams, right down to the Cuban heels..and always

particular about things right down to the hair-oil.

Back in my youth,

when a bad case of industrial diarrhea forced me from the building

industry for a short break, I took a job with that drilling supply

company, building specialized shipping crates for machinery and drilling

equipment…it was a dumb job, just what I wanted…didn’t have to think

much, and we could play “shoot-‘em-up” target practice with the

air-compressed nail gun (they didn’t have safety locks those days)…one

of the shipping clerks would make a dash past the timber racks and I’d

try and get him with the “rat,tat,tat” nail gun…great fun!

Come

smoko, a group would gather and yarn about life and things..you

know..the usual crap . One of the sales reps used to work on the rigs

and one day he told about this chap nick-named “Precious”…I’ll relate it

to you as best I remember he told us .

Doug Orchard’s (Orchies) crew

had set up camp on a grid-line somewhere way out west of Longreach in

Qld’ in January..Lethargy usually sets in by that month in Summer, due

to the heat and isolation from all forms of civilized discipline.

When the camp was first set up, Doug discovered an old, dry bore hole about fifty yards from the camp.

“This” he thought “will do for a dunny-hole and will save me from setting up and drilling one”.

He

asked the “cocky” about using the old bore hole and the farmer shrugged

and said; “Sure, why not?” So the rickety site dunny was erected over

the old bore hole. This toilet hadn’t a roof because of the horrors of

being trapped in such a sweat box under an unforgiving sun with a bad

…..bad conscience (shall we say?).

It was January and a Sunday and it

was hot so that most of the team were sitting outside under the

mess-van annex in canvas deck chairs having a cold beer. There were a

couple of dogs lolling about there too.

Who should turn up but

“Precious”…Actually , they could see someone approaching by the thin

streak of dust rising over the dirt road on the distant plain rising to

the low plateau on which they were camped.

“A fiver it’s Precious” one of the men spoke languidly to no-one in particular.

“You’re on”..replied Bob.

When Precious stepped out of the truck, a fiver changed hands with a fatalistic sigh from Bob.

“Hello chaps” greeted Precious, without a hair out of place and a smile on his face.

“

‘day Precious”..they replied and greetings were exchanged in

monosyllabic words as only can be understood by those who have spent

time in the outback and mixed with the many and complex eccentrics that

inhabit those remote parts…and it is said that an open mouth only

attracts flies.

Precious settled down in an empty chair and partook

of a nice cool beer…only he drank from a glass..his own..After a short

interval of idle chatting, he indicated he wanted to use “the

conveniences” (his words).

“Down by the big tree” Bob pointed with his chin.

“Flamin’ long hike” exclaimed Precious.

Bob shrugged and flicked the ash from his cigarette.

After returning from the dunny. Precious complained ,with a screwed-up nose ;

“ I can see why you’re so far from that dunny!.. Geez, fellahs, it’s a bit on the nose!”

“It don’t bother us, Precious” said Bob.

“No..I s’pose it wouldn’t” said Precious with a sigh “anyway , I’ll do you a favour and burn it out….er..where’s some petrol?”

One

of the men motioned to some five gallon drums in the shade of a

lean-to. Precious doffed his Akubra, took one of the drums and headed

down to the toilet.

As Precious told his story later…”A man’s a fool.

I’ll tell you what happened..I emptied the whole drum down that

hole..say; How deep is it?…you don’t say…well, no wonder I didn’t hear

it splash on the bottom. Well, after I’d emptied the drum, I lit a match

and threw it down..nothing happened (it musta blew out before it got

deep enough) I tried again and still nothing, so I got a few bits of

toilet paper, lit them and dropped them down and stepped back…still

nothing!!??..Well, I don’t know what made me do it, I shoulda’ known

better..but I gingerly leant out over that hole and looked down…and

suddenly..god! it was frightening .”

Doug, was up at the rig and

arrived at the mess van as Precious was walking down to the dunny with

the drum of petrol. The boys told him what precious was up to. He just

grunted..”Good luck to him” he thought and sat down to a beer with the

other blokes.

“A fiver says he’ll blow himself up”

“You’re on” said Bob.

He’d

only a couple of draws on his beer when suddenly.. and it’s strange

how, at a distance, the action happens before the sound reaches

you..like a person chopping wood with an axe, and you can see the axe

fall before the “chop” sound reaches you.

They saw Precious’ Akubra

hat flip, spinning away out the top of the dunny like a frisbee with

bits of snowy stuff floating with it, then the ‘WHOOMPH” of the

explosion and Precious crashed out of that dunny, ‘swimming’ sort of out

of the smoke and coughing heavily. Bob reached into his pocket and gave

over the fiver…Doug, not to miss a chance at dry humour asked ; “Baked

beans for tea again tonight , Bob?”

The sales rep said they all just

sat there like they were the audience in a theatre watching a show.

Precious came stumbling back shaking his head and cursing..when he got

closer, they could see bits of toilet paper and..stuff..stuck all over

his face…”an’ his eyebrows were all burnt off”

“You’re gonna have to change your after-shave, precious.” Bob said, shaking his head.

Anyway,

that’s why you’d know Precious if’n you met him…He’d probably tell you

his tale if you showed curiosity in his complexion.

He’s a bit

nervous around petrol these days, and even traded in his old petrol

driven truck he swore by and bought a diesel.. “Better mileage” is what

he says.

The Rose and The Plough.

In the back-blocks of the mallee

‘Neath Mrs. MacFarlane’s sill,

Grew a rose bush many years ago,

(I ponder it’s there still?).

“ ‘Twas planted for my Louise

When she was newly born.

I mark the contrast of the rose:

The blossom above the thorn!”

MacFarlane ploughed the dry soil of that block

With machines tended of sweat and tears.

While Louise blossomed with the rose

All through her growing years.

But age slowly wearied him,

The years of labour took their toll.

So young Tim Brey that season worked the plough

And a bumper crop did sow.

Creeping fingers of evening shadow

Edged ’round mallee scrub and tree,

As Tim drove through the station gate

And Louise, he did suddenly “see”.

One warm evening ‘neath a mallee tree,

With the harvesting finally done,

The “old man” grumbled toward the house

While Tim and Louise talked on alone.

A silence fell after all was talked about

With dusk thru’ dust aglow.

Tim clasped the bough above her head

And leant toward his “rose”…

…The wind would move the fields of grain,

A swollen swirling “sea”:

Of “ebb and flow” in the crops

On the Breys’ new property…

Themselves now grown so old,

Their children too have flown.

But still the rose bush given

For their wedding blossoms on.

The mallee is not so prosperous,

The price has gone from wheat.

The farm is dusty, the house too old;

Deep lines fan Louise’s cheek.

Tim Brey harrows still with his plough

The “home paddock” into rows,

While Louise battles with their accounts,

As dust silently falls-on the petals-of the rose.

Clarice Proudthorpe.

A REFLECTION ON A ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY FIVE YEAR OLD TRAGEDY.

About

five miles east of Mannum, on a quiet dirt road, stands a one roomed

school house. It has four windows, two doors and a corrugated iron

shelter shed at the rear. There seems always to have been an iron rain

water tank by one wall, and once a flag pole, which flew, up until the

early nineteen hundreds at least, the union jack of the British Empire,

stood amongst the sugar gums.

Sitting in its one acre block of land,

surrounded by paddocks, it is a quiet, out of the way place, but there

is always a little traffic passing by. How many people who travel along

that road, I wonder, know why the school stands where it does.

This is its story.

My

great-grandfather, a farmer of the Clare Valley, married an Irish girl.

Her name was Mary Ann; my great-grandfather was William. They raised

ten children – five girls, and five boys. Tragedy struck when typhus

caused the death of their eldest daughter; childbirth took the lives of

the next two.

In the 1890’s, the family, with the five boys and two

surviving girls, moved to the area east of Mannum, where former station

country was being divided into 500 acre blocks.

The four eldest boys

of the family bought land in this district; three of them married and

raised families of their own. The two girls married local farmers; one

of the girls living to over a hundred years of age, the second dying

after the birth of her third child.

The tenth child of the family, a

boy, was younger than his brothers and sisters, and because there was no

school in the area, went to Mannum for his schooling – a long walk each

day for a child.

In the year 1899, on his way home from school, he went with a friend for a swim, got out of his depth, and drowned.

Determined

to prevent further tragedy, the local farmers petitioned the government

for a local school. Their Petition was denied.

Despite this setback,

enough money was raised to hire a stone mason. A local land owner

donated an acre of ground, and the school, constructed of the local

limestone, was built.

It was opened in 1901, the year in which Queen

Victoria died, and the long Victorian era drew to its close. The

government sent teachers, often young women, to teach at the school;

most boarded with local farmers; in later years, they cycled from

Mannum.

But the one roomed building was much more than a school. It

was a place for local gatherings; dances and social evenings were held

there, Arbor Day and Australia Day celebrated, football matches were

played. It hosted afternoon teas and a wedding reception; my grandmother

played the organ for the Sunday School. During the Great War, a local

lad who had enlisted was given a farewell at the school; auctions were

held to raise money to help wounded soldiers.

At the end of the

school year, parents gathered to watch their children presented with a

certificate, which stated that they had completed a year’s schooling,

passed their examinations, and would move to a higher class.

‘Young

lady’ teachers in long gowns taught seven classes of children to read

and to write, to learn arithmetic, history and geography – took them for

nature walks along the quiet country roads; taught them ‘drill

evolutions;’ possibly a form of calisthenics.

She had also to keep

the school room clean and the wooden floor scrubbed, and in the winter

time, a fire lit in the fireplace. the thick walls still keep it cool on

even the hottest of days.

Children who walked, or rode a horse to

school, used slates to practice their writing and their sums. Large

maps, much of them coloured pink, on the walls, taught them that they

were part of a great Empire.

The faces of those children still gaze

solemnly at us from the photos on the walls of the school room; class

photos of 1904, 1915, 1927 and on into the thirties and forties; girls

in long sleeved dresses and pinafores; boys in heavy jackets and short

trousers.

What were their stories? Many left the mallee – life there

was hard, and there were better prospects in richer states. A few

remained – their descendants still farm the same acres, though the

paddocks are much larger these days, and machines have taken the place

of the horses that were used for the hard toil of clearing and ploughing

the soil.

And the child who died? His name was Frederick Albert Haythorpe, he was 11 years old, and that is all that I know of him.

It

was March when he died. Was it a hot March? Did he just want a swim

before he walked home for tea? The road from the river and up the Murray

Bridge road is a long, slow climb for legs that were only eleven years

old.

The home where he lived is a heap of stones, all who nurtured and loved him are gone.

But

the land that he knew and the tough mallee trees endure -the road that

he walked still throws its pall of dust over the roadside vegetation

each summer.

And the schoolhouse stands yet, a silent memorial to the

tragedy of his death, and a testament to hard toiling mallee farmers

who were determined that no more children would die because there was no

school for them, who stood together and said, ‘This can be done.’

Helen Tuxford.

LISTEN

Listen to a magpie singing,

Singing sweet, and singing clear,

If I had wings,

I’d fly there with him,

Leave this weary world below.

Listen to the children playing,

Running, laughing, in the sun.

Where will their

Light footsteps lead them

When their childhood days are done?

Listen to a magpie singing,

Singing then, and singing now,

A golden tune,

That echoes ever,

A song for you, a song for me. (Helen Tuxford.)

A Simple Love Affair. (Joe Carli.)

Years

ago I was “doing a reno’” for this Greek bloke who was managing the job

for his daughter…who was the owner of the house. She was as the lovely

“Anna” described in the story below. She would come around to the job

every few days and talk to the old man about design and so on..I never

spoke to her and only saw her from a distance..she always wore a jacket

thrown over her shoulders in the Greek tradition, so I didn’t know she

was a thalidomide child.

“ Is your daughter married? “ I once asked him.

“No!!..she never marry!” he replied with a twist of his face. I was puzzled.

“What do you mean ; never?” I persisted.

‘What?..You not see?..no arm , no marry”

“What do you mean : ‘No arm’ ?” I queried him.

“She have no arm..just a stump..her mother she once take that pill..tha…tha..” I twigged.

‘Thalidomide?”

“Yes!…that’s it..and she have no arm…so, no arm no marry…”

So

I have built a story around that moment, that awful reality…and I have

moved the story to the mallee, to another older time and place.. Why

not?..I too desire a better ending than what the sour cynicism of that

old man offered. Why should there not be a..a simple love affair, set in

a mallee town with two young people? Yes!..let us create our own

“reality”..our own desire if only for one moment, one afternoon! And

even as the some may attest; that only 1% of people are interested…so

what!? Let it be just that 1%, for that small number is powerful enough

to move Heaven and Earth to a better place in the heart of humanity even

against the greater odds of the indolent 99%.. We must accept that our

“Art” is failing us..there is a loss in western interpretation of

“romantic inspiration”..by romantic I mean that desire for the

imaginable reality rather than the “cynical certainty”..bad things in

life are a given, but hope is always there…without desire, there is no

hope..without hope there is no life.

So, dear reader..as the story unfolds, let us desire…

A Simple Love Affair.

When

Anna fell in love it was not without a good deal of caution. You see:

Anna was a thalidomide child and though she had grown to a beautiful

woman, her left arm, stunted just below the elbow with two stumpy

fingers threw a “check” on any chance of an out-going personality. So

when Anna fell in love with Harry, it was a long, cautious

apprenticeship.

Anna worked in partnership with her cousin; Bella,

running a small general store in a country town out in the mallee. They

named the business: “Annabellas” and it was a good business, an honest

business well run that reflected the determination of the proprietors.

Anna

was twenty- eight years old, of medium height with a slim face and long

black hair down to the middle of her back. Let no-one doubt that old

truth that a woman’s hair is her crowning glory! Anna was a fiercely

independent woman and held no truck with self- pity, yet , there was

that natural reserve that sets aside those with physical disabilities,

that je ne sais quoi, (that certain something) of the spirit that

brackets their behaviour, a caution in manner and speech that is

sometimes sadly lacking in other, less impaired specimens of “Humanus

Grossness!” However, in matters physical, Anna never failed to pull her

weight, and was always ready with a quick witticism if her stunted limb

failed her. Yet, she never developed a long term relationship with any

boy from the district. Oh, she was not the type to lament this reality,

nor did she overcompensate her disadvantage with lasciviousness! She

just had a well-balanced perspective of the situation and the close-knit

societies of country towns of those times seemed to lock the young of

that era into behaviour systems that exclude, in the majority, any

dabbling in relationships away from the physical and physiological

norm…sadly, any who went against this “norm” had to leave the community

for the wider understanding of the cities. Not that this is an

unforgivable fault, for a country town is born of the earth and survives

from the earth and therefore any deviation from the “pure state”

(however illusory that is) of natural wholeness is, if not condemned;

shunned. To put it simply, as old Smith once remarked with a worldly

shrug: “No arm…no marry.”

Harry was of the district, once. His family

sold up and moved away many years before and now he had moved back to

take over the garage once old Peter Porter retired , for Harry was a

mechanic. Harry was thirty- three years old when he moved back to the

district. He was tallish, well-built (for a mechanic!) with short fuzzy

hair and a fixed smile on a generally happy face. Harry had no chip on

his shoulder (no axe to grind!) and a healthy disposition. Just the

person to run a garage in a small country town! Why sneer? he created

neither moon nor sun, nor shook fist at others fortune, yet, Harry

suffered that most disabling of conditions: He was shy! Oh, he could

slam the gearbox of any tractor onto the block of the engine, with

appropriate epithets and wiping of greasy hands and shout to a farmer

across the road:

” She’ll be right this ‘arvo Clem’ ,”..but, stand

him in front of a social crowd in the Hall meeting, or a pretty woman

and he’d fumble about like a cow in a mud-hole. So consequently, one

rarely saw Harry outside of overalls and armed with a spanner… except

for the annual football club ball. (you don’t like football?….tough,

millions do!)

Harry’s garage was three doors down from “Annabellas”,

consequently there was frequent conversation concerning pies or pasties

or pieces of string between Anna and Harry. One of these centered around

the aforementioned Ball..

“Getting close now.” Harry said in an offhand way.

“Yes” Anna checked the list of groceries. Harry shifted foot, like a horse resting.

“Who are you going with, Harry?” this threw him a little as he was about to ask Anna the same question.

“Huh,oh!…well, myself I ‘spose…you got someone?” a slight inflection of voice.

“Yes….”(drop

of mouth from Harry)”My father”. ( mouth picks up again) Anna ticks the

last entry on the shopping list and looks up expectantly.

“Oh,..right.”

Harry fumbles in his top pocket and withdraws some money. He counts out carefully on the counter saying as he does so;

“Well

I was wondering if you’d care to go with me?” Anna raised her eyebrows,

the merest flicker of a warm smile at the edge of her mouth.

“Hmm,..but what about dad?”

“Oh,..he’d come too.” Harry quickly replied, lest there be insurmountable opposition. His eyes appealed.

“Well….” and here the usual reserve stalled her, but this time she relented. “I’ll ask dad if he doesn’t mind… ”

“And you’ll come if it’s ok with him?” Harry persisted unusually but fearfully.

Anna thought, then looked at Harry closely.

“Yes.” she said. Harry seemed to lose a frightful burden just then, for he suddenly straightened up and smiled.

“Righto!..”he

quipped confidently,” I’ll…I’ll catch you later”. and he left the

store..he suddenly returned sheeplishly to take his groceries. He

gathered them up as if they were a clutch of puppies, smiled, and

quickly retreated to his greasy nirvana.

Well, the night out at the

ball went smoothly, as neither Anna nor Harry were wild ragers and would

rather dance than drink. So consequently there were other social events

that they escorted each other to ,for Anna would invite Harry as much

as vice-versa and so it became accepted that Harry and Anna would be

matched on invitations ipso-facto , so do small communities naturally

react…and their mutual company gave confidence to the two companions as

they grew more familiar with each other’s idiosyncracies.

No more

than a stage of evolution I suppose ( but you knew this was going to

happen; quiet man meets beautiful, flawed lady, they fall in love, get

married etc, etc and so forth!). But there was one hindering factor in

this quaint affair of the heart, something most of us in our safe,

sheltered worlds have never to face or confront: the thalidomide

arm….the flaw!..ah!. as a flaw in a diamond will deflect the light so

does a flaw in a human disturb the smooth natural flow of emotions . Why

even an embrace would draw attention to Anna’s stump arm , she; the

embarrassed frustration of not being able to rub a caressing hand over

Harry’s shoulders, he ;the knowing of this frustration in Anna and the

clumsy overcompensation on his part, the actions of dismissal of the

offending limb! Yet that limb was her, or a part of her, as much as a

leg or nose or breast! She knew it, he knew it but still the dammed

thing would obtrude, out of all proportion into their consciousness. But

then again, neither of them could or would broach such a delicate

subject, such are the cautions in romance, the halting secrets of the

heart: “will I? should I?” and so neither is done.

I’ll have to

mention that long before Anna had met Harry, she became aware of this

nagging feeling and once even, had seen a doctor in the city with a view

to amputation of the offending limb, reasoning that it would be easier

to explain away an injury than be eternally on show as a “freak”.

Fortunately (for she was strong willed) this idea, born on the wings of

youthful despair, was soon cast aside as ridiculous and childish. And

she grew stronger for it. Oh! that us with body complete could draw on

such fortitude, when even a slight ailment of body or soul sends us into

paroxysms of complaints..Oh frail souls ! Oh weak heart!

So into

the summer months under a vacant sky rafting on a sea of mallee bush did

they continue with their courting, a gentle affair with neither tryst

nor jealousy but as two labourers with a common goal they met ,

socialised and parted. And then one day Harry “popped ” the question.

And Anna accepted and indeed, why shouldn’t she?….She desired children, a

home to raise them in….but should one feel a little raising of hackles

at this servile “acceptance” of a woman’s lot? Should she rebel at this

“presumed” social construction?..for after all it is but a story..a

facsimile of a life..ah!….permit me a smile….and I ask : do we really

believe the world and all in it waits with bated breath for miraculous

revelations from those that would have us stride with determination down

this or that corrected path?….Have we not all waited…and yet inside

each of us there is that strange hunger, that desired want for a kind of

fulfilment..and so we may now smile… Yes. Anna accepted, yet there was

one unsolved dilemma left in the air and she meant to speak, felt she

had to speak to Harry about it soon.

Saterdee arvo, is there a more

pleasant occupation than being young and alive in the summer with work

behind you on a sunny Saterdee afternoon in the country?… Harry thought

not as he stood wiping his greasy hands with a bundle of cotton waste

outside his garage. A smile on his dial, a song in his heart and whom

should he spot walking up the pavement toward him?…

“Anna!” he called

with glee.”Where’re you off to with such a pretty bouquet?..not another

secret love I hope?” and he laughed …and gosh, didn’t she look

pretty….her warming smile above the multi hued bouquet.

“It’s for mothers grave actually”, she said. Harry gulped at his over exuberant gaffe!

“Oh dear, pardon me”, he gasped. Anna smiled now.

“Don’t

be silly, she’s been dead fifteen years now”. and she fussed with the

arranging of the flowers”I’m going out to her memorial now, ..you want

to come?”

“Say no more.” and off they went.They had hardly driven a hundred yards when Harry suddenly ducked his head below the dashboard.

“What are you doing?” frowned Anna. “Just keep going it’s Noela Maletz! I said I’d have her car fixed this arvo!”

“What, are you afraid of her?”

“Dammit, the whole town’s afraid of her.”

“Whatever

for? she’s a lovely lady….she just knows what she wants and isn’t

afraid to say it.” Harry raised his eyes to glance backwards out of the

car.

“Well, if she saw me driving around instead of fixing her car,

she’d want my guts for garters! I’d lend her my car, ‘cept it’s out of

action.”

“Your car?! it’s the worst bomb in town!”

“Oh yeah. an’ I bet your cupboards are empty!” they were both silent for a moment then burst into simultaneous laughter.

“The

carpenters house is falling down around his ears!…. Anna cried …”And

the cobbler has holes in his shoes!…Harry laughed..”And the tailor has

the arse hangin’ out of his trousers! they both choked in fits of

laughter ..”Ahhaha!..but it’s true!” cried Anna.

The car pulled up at the cemetery gates, Anna jumped out, Harry made to follow.

“Wait there, just be a minute.”

“But I thought you wanted me to come?”

“To her memorial. yes, this is her grave. We’ll go there next, I’ll be right back.”

It seemed a mystery to Harry, “Graves…memorials…same thing.” Anna returned in a moment and they started going again.

“I just had to replace the flowers.”

“So where is the memorial?”

“On the farm, dad made it just after mum died, it is rather unusual…we’ll be there in a little while.”

The

family farm was ten kilometers out of town on a side road. After the

black ribbon of bitumen, turning off onto the dirt road was like turning

into a photograph:

“And I mark how the green of the trees,

Matches the blue vault of the sky….”

The

low stunted mallee trees leant in from the shoulder of the road, the

fronds of slim leaves dipping over the limestone gravel. Blackened

twists of discarded bark and twigs littered around the knuckled boles

and roots. Here and there amongst fallen trees, rabbit warrens displayed

their sprays of fresh diggings white and musty amongst tangles and

hummocks and if the eye is quick enough, a flash of cheeky tail can be

spotted sporting behind tussocks of native grass, or even a round-glassy

eye spying unblinkingly for any sign of danger, then a quick

“thump-thump!” signal to other rabbits and scurry down the safety of a

burrow and braer rabbit says cheerio for the daylight hours!

Anna

drove off onto a track with a gate in the fence, entering the paddock,

she drove alongside the fence till she reached another gate, though much

smaller than the first, like a front gate to a house, there was a

carefully manicured path with white stones edging it, that led on a

gentle slope toward a grotto-like cavern at the bottom of a basin in the

surrounding land. Anna led them to this singular spot, for Harry had

never heard of it before. They stood at the lip of the soak, green

kikuyu grass spilled out from the sunken pit, it was circular, about

thirty feet in diameter and the front sloped down to a pool of cool,

clear water mirrored under an overhanging lip of limestone six foot

above the pool. To one side of the pond, in a well tended, circle of

earth, was the most beautiful flowering yellow rose-bush Harry had ever

seen! He stood at the lip, gazing around at the scene.

“How long has this been here?” he asked amazed.

“As

long as I can remember, Mum and Dad used to bring us here in the hot

weather and we’d wade in the pool. After Mum died, Dad and us kids made

it into a sort of memorial….she liked the place so much…”The oasis” she

called it. Dad also pumps water out for the stock in the dry weather. It

never seems to run dry.”

“And the rose?” Harry asked.

“I planted that….a rose for incorruption….she liked yellow.”

“It’s a lovely place….peaceful.” Harry spoke dreamily…Anna took out a pair of clippers and went toward the rose.

“Come…”she called “Help me cut some roses.”

So

they stood, she cutting, he taking the blooms. With her stumpy arm Anna

deftly moved the prickly stems out of the way, her long, dark tresses

falling this way and that over the blossoms so sparkling yellow in the

sunlight. Now and then a petal would dislodge and fall spiraling to the

earth, so silent was it there you could almost hear- the petals touch

the soil.

“Harry?” Anna spoke as she concentrated.

“Mmm.”

“What

do you think of my arm?” she didn’t look at him as she asked, she was

listening to the tone in his voice. Harry hesitated…he knew what she

meant and was delving into his emotions .

“Your arm…”He repeated almost to himself. “I..I think it’s unfortunate but I don’t feel put off by it.” it was a start.

“It’s

a burden, Harry, always has been, always will be, strange how sometimes

it feels like it isn’t a part of me, so different, when I wake

sometimes I look to see if it was just a dream.”

“Does it make a difference to our relationship?” he asked.

“In

its clumsy intrusion, you know that.. yes..more later perhaps than now,

when our company grows so much more familiar and little things come

between us.”

Harry didn’t answer, but shrugged his shoulders. Anna stood facing him and placed her hand on his shoulder,

“Harry, we are about to be married….to have children…from there it’s a long road ahead..”

“I..I’m

sure we can do as good as other people in their marriages. ” Harry

gently replied. Anna turned slowly to one side to stare at the rose.

“I worry, Harry, that any children we may have will not also be affected.”

“It’s not passed on .I believe.”

“You

believe, but who knows!” Anna’s emotions engulfed her and she dropped

her head crying “ Who knows,Harry…it killed my mother, the

responsibility she felt for it…if..if I bore children that were

deformed..”

“Oh I’d hardly call….”Harry interrupted.

“Yes!” Anna

persisted “deformed, for that’s what it is Harry, deformed…and I would

indeed blame myself for…for..” and she turned her tear-stained face to

him..

“Oh, Harry, If ever there was a time to back away from your

commitment, it is now!…I wouldn’t hold it against you…but marry me not

with naivety, nor…for gods’ sake ..pity!” and she turned to him with a

steady challenging gaze. Harry reached for her stump-arm and

deliberately took it in his hands. she automatically went to pull it

away but he held it tight and though she could have withdrawn it. a

stronger force held her.

“Anna….would you think me so simple so as

not to see the complications that lie ahead in our marriage?…for

marriage it shall be, lest thou refuse me…and would you hold my feelings

for you so lightly that you could see me casting them aside, like a

discarded rag , for nothing more than this stunted limb? For if that be

the measurement of grace, where does one start.? Do I compare the beauty

of your eyes against size of your feet?…or grace of your step to the

lobe of your ear?….hearty laugh against dirty nail?..and where do I

stop?..” He rubbed Anna’s two stumpy fingers gently “If I gaze into

your eyes, do you see pity, greed, selfishness?..look now, Anna , don’t

turn away, look!…you see affection..no pity, no naivety, no denial…I’m a

grown man….l love you, Anna, do not misjudge me nor deny your own

feelings but just say you will marry me.”

Harry raised her stump-arm

to his lips, the two tiny fingernails painted red like those on her

other arm, and kissed her fingers. Anna’s face contorted to one of

weeping happiness and she flung her good arm about Harry’s neck and

there they embraced while standing over the rose bush.

“Yes, Harry,” she murmured in his ear” I will marry you, yes!”

The Third Alternative.

Part Two.

Our house is situated on the side of a hill, almost at the summit. Behind us, pine dark peaks, with their springs and cold, narrow streams, march heavenwards. Below are enclosed fields, and the tarn which supports water fowl and flocks of ducks; beyond, the bare slope with its solitary almond tree where we bury the dead from Clach Thoul.

More dead than living come to us, and Hagraade, the sewer, dilingently stitches shrouds for them, and when they have been lain in their rough earthen holes, Dubricius sprinkles a little holy water on the turned up soil, so that those beneath do not lie on unsanctified ground.

And though no stone marks the place where each soul sleeps, I like to think they are peacefully there, on that quiet hillside, with the grass growing green in the winter, and the gentle wind blowing through the almond’s branches when the summer comes around again.

Aviv drove the wagon to the grey roofed building where one of our house, Tenes, receives the dead of Clach Thoul. A pious and often silent man, he washes each body and places it in a simple linen gown – ‘ clean and decent for its burying,’ as he says.

I watch him at his work, and wonder much at the care that he shows to such poor heaps of flesh and bone. But looking, I see the pity in his eyes, and am humbled, and know that I have much to learn before I reach the stature of such men as Tenes and Aviv.

When we reach the inner court, Aviv carried the one living man to the hospice, then went out, in the evening light, to unharness the horse, to dig the graves and help bury the dead. He prefers to work outside, in the fields, where his strength and endurance are most needed, and in the orchards and vegetable gardens with which we have surrounded the workshops and barns, for it is essential we be as self sufficient as possible in most of our daily needs.

In the hospice, I helped Pileb, who is a little older than I – he and I are the youngest of our community – to wash and clean the man brought from the wagon, ready for Waltheof, the healer, to attend to him.

The man lay, silent and exhausted, on the hard wooden bench where Aviv had put him, one arm hanging awkwardly over its edge. I placed the arm on his chest, that he might be more comfortable, and, while Pileb began to remove the remnants of the cothing that he wore, and the remains of his boots, fetched hot water and towels.

The sick man was conscious, as much as his were not closed. But to every word that Pileb addressed to him, he made no answer, or even sign that he had heard, and I began to wonder if he was insensible, and his open eyes just a natural reflex.

But when Pileb picked up a knife to cut away the cracked and worn leather of his boots, his eyes flicked at once to the knife, and I knew then that he was conscious and aware, but was, for a reason of his own, ignoring us. And while we worked to cleanse him of the grime which clings to the unwanted, he stared, with fixed gaze at the further wall, neither hindering, nor helping us in our labours.

At first we talked to him, Pileb and I. We asked him a few simple questions, spoke to him reassuringly, for often the people of Clach Thoul are disoriented upon coming to themselves in strange and unfamiliar surroundings. But as there was no response, our words began to sound too loud in the quiet room, and we too fell silent and worked without speaking.

He was very thin, the man we had rescued. But it was a leanness caused by poor and scant food, rather than that of long illness. He was not as wasted as many who had suffered the privations of Clach Thoul – he still retained some muscular strength. And I was surprised to see that he was not an old man – there was colour in the hair upon his body, and that which grew on his head, once freed of the dust which coated it, it was only lightly touched with grey.

Presently, by which time he had been sponged with the tincture which we use to fend off disease, garbed in the simple gown that is provided for the hospice, and moved to one of the beds, Waltheof arrived, and we stood aside respectfully while he made his examination of the new arrival.

Waltheof is a gentle and very devout man – Dubricius says he is touched with the spirit; but even Waltheof’s reassuring presence elicited no response from the man in the bed.

‘He might be deaf,’ Pileb suggested, speaking quietly, but Waltheof, his eyes watchful, slowly shook his head.

‘No, this one is not deaf.’

‘Could he have lost the capacity for speach?’ I asked, puzzled by the man’s continued and determined silence. ‘ Is it that which ails him?’

Waltheof was still looking thoughtfully at the worn face against the pillow.

‘ It may be, child, that he has no inclination to speak.’

‘Does he fear us?’ I said doubtfully. ‘We intend only to offer him such care as is within our means.’

In the bed, the man lay wuietly, his eyes closed; hands limp by his side; he had on him the air of one who had survived an ordeal and only wished to rest.

Waltheof covered him with the sheet, and beckoned us from the room. In the corridor, he said quietly, ‘He is dylin, my son.’

“But of what?’ I have seen death, many times, in the hospice. But never of a man who had retained some strength and who would, given care and nourishment, recover; in my ignorance, so I thought. ‘He has no sores, or fever; no signs of disease; how then, can he be dying?’

Waltheof smiled, gravely and a little sadly. ‘What can we see of a man by looking at the outer husk? We know nothing of the true and inner self; whether that self be honest, or lonely or cruel. I do not know why this man is dying, or why he has no words for us. But the soul can sicken, even as the body will. Perhaps he has no notion as to what is to become of him here, and is afraid – perhaps his silence is his only defence.’

‘If that be so, we can help him,’ Pileb suggested eagerly. The fevour to men, to heal – these burn brightly in Pileb. He said, ‘We can sit by him, so that he is not alone with his fear. Pray – offer him words of faith and hope to allay his suffering.’

But Waltheof looked at him with a frown. He said reprovingly, ‘No, Pileb. It is not our place to intrude upon a man at such a time.’

‘But surely it is not an intrusion to ease the burden of the ill-fated,’ Pileb protested. ‘Or to try to save one who may know little of mercy or grace.’

Waltheof took an arm of us each, and led us further down the corridor, so that we were well out of hearing of the hospice.

He said sternly; speaking more to Pileb than to me, ‘This is a man’s last and most desperate struggle – the time of his dying. All other battles that he has faced are as naught when he is confronted with his own mortality. But each soul must choose its own destiny, just as we choose our own path through life. Do not trouble thereof, one who is suffering, with clumsy offerings of teachings which may have no meaning to him. Do the little that you can for his ease and comfort, and leave him to find his own measure of peace.’

But Pileb, I could se, was not wholey convinced by these words, and Waltheof was, without doubt, aware of this also. He put his hands gently on Pileb’s shoulders. ‘Pileb, my son, to be a healer ios to aquire wisdom and humility as well as the art of healing. There comes an hour when the best one can do is nothing at all. Lear to recognise when the spirit has run its race, and has no further need for the shell that harbours it; when death is the only way forward.

He dropped his hands, and said, addressing us both, ‘Go now and attend to the one who needs our care, for he is exhausted from the heat and from lack of food.’

“As much of the healing draught as hes can take, and some light food – broth, and a little bread and fruit. Be sure that he drinks plenty of water, and add a little honey to the lime and the balm to soothe and strengthen him.’

Pileb, I think, was half tempted to protest again, but he has too much respect for Waltheof to question his instructions. He inclined his head, instead, in acknowledgment, the nudged me sharply, for, lost in my own reflections, I had forgotten the customary courteous salute.

Waltheof nodded kindly – he is always kind – and went on his way, and Pileb and I, both silent, turned back to the main chamber of the hospice.

Helen Tuxford. (To be continued)

The Tower.

The Tower.

He fell,

As mighty edifices do fall,

And death made a mockery of him,

As it makes mockery of us all.

But I was just a child of Shinar,

On the plain where The Tower was built.

Bored with a sedentary life,

They hungered for something to adore.

It sprung from the soil a shimmering phallal,

Upon it they lavished their skills

And they named it Babel.

Oh, how it climbed toward the heavens!

While we fed off the spoils of Mother Earth,

The fruits and wines that gave us birth

With n’aer a thought of impending death,

So was the pride full in our hearts.

I asked of my Father, a mason there,

“What the reason for The Tower?”

“In your wildest dreams” he said “you will not want,

And in your steps you will not falter,

We have built and paved a path to heaven,

We have gilded mankind’s altar.

Precious stones from far Afghanistan,

Quoins of coloured marbles of Kazakhstan

Pearls from the depths of The Euxine Sea,

Onyx and alabaster barged down the Nile,

These riches have we brought to thee!

Heaven is our gate, Hell below our feet,

We stand poised to challenge the Gods

Never more to yield to a defeat.”

I was a child of Shinar when the Tower they built,

And never was there a more united cry,

A more singular and determined voice,

“Babel!” they cried, “Babel! You are ours!”,

Voices like sea-waves crashing eternal upon a beach.

And they built onwards and upwards that mighty tower,

The riches of the Earth they did devour,

With no thought of rest…nor honour,

We poured all into that mighty edifice.

Our leaders, as toward heaven it thrust,

They called down to us, encouraged us,

“This is of you” they softly called.

“This is by you” they softly persuaded.

“This is for you” they softly whispered.

And that triple reassurance won us,

And we worked and laboured for that goal,

“Babel, Babel!” we cried and we worshipped the ideal,

And we never wondered when our own plates went empty

Why some others were always filled,

Why THEY were able to lavish aplenty,

While our plains and wells went dry….

Then it fell.

As soft as a tremor, violent as a quake,

It fell because of one small mistake.

It fell when we suddenly came to see,

After climbing, climbing so high in that ecstasy,

Those Gods whose heaven we were calling home,

Were neither singular..nor divine,

But were a made creation of our own!

WE made the Gods of OUR own image,

NOT the Gods of us!

WE made heaven of OUR own wants and desires,

Our leaders fed us of our own language,

And fanned and fuelled our tangled runes,

Spoke in riddles of strange but familiar sounds,

Until we could no more understand their tongue,

And then we saw..our work there was done.

We cast away our tools,

Cursed each other as fools,

And wept….

“Oh Babel, Babel..why has thou forsaken us”.

But too late..too late..it is gone, it is bust..

Babel, our hopes, our dreams, our lusts,

Babel, our creation, our immortal soul,

Has but gone to dust….

We were children of Shinar when first The Tower was built,

We are adults now…awash in a sea of guilt.

Erik Heldzingen

Invitation!

To anyone interested in this publication, or to those

wishing to contribute to the continuation of a literary magazine

dedicated to the region of the Murray Mallee and Murray River and its

environs. We, the editors of this publication invite you to send

feedback to our email address or to simply telephone us on the supplied

number to either make comment on the contents, presentation or give your

opinion on how best to present the cultural variations, past, present

and future of this region.

Our aim is to create specific cultural /

social identification of the region from the eastern hills face, to the

river..from Morgan to Mannum, by using story and social history to

imprint this area with its own indelible “watermark” that says; “THIS is

the Murray Mallee region”.

So please, if you want to contribute to

future publications or simply get in touch, our email is :

jaysee423@gmail.com or telephone : 85652256. And ask for Joe Carli.

Comments

Post a Comment